Narmeen Ijaz on ‘Wild Wild Country’

The 2020 presidential elections marked a significant milestone in U.S. history as the shift of power between parties ensured, albeit temporarily, that a democratic system has prevailed in the country. However, the tumultuous incidents that preceded the election and inauguration of a new president raised significant questions over some of the long-standing sociocultural and political ideologies upon which the U.S. democratic system was established and grew. We now urgently address questions about the stability and adaptability of U.S. democracy. We wonder how effective our legislative safeguards actually are against injustices and discriminatory attitudes, speech and acts towards racial minorities and immigrant populations. And we balance the answers to those questions with others about what constitutes freedom of speech in and for a culturally diverse nation.

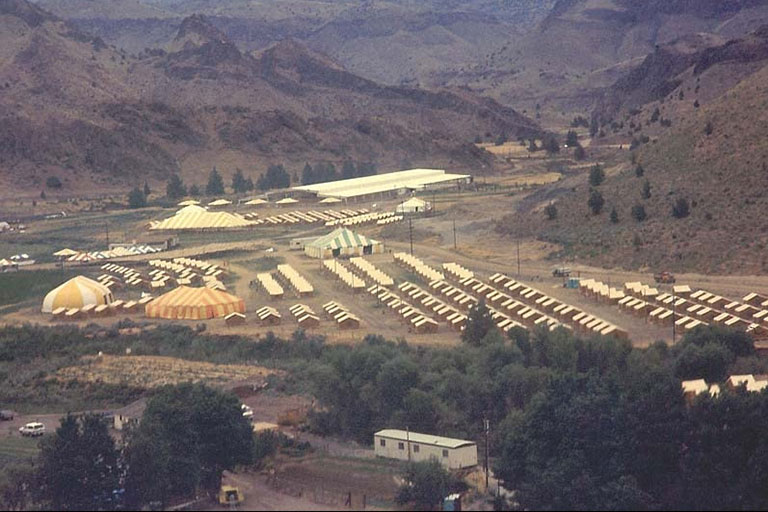

In times like these, it is useful to revisit Maclain and Chapman Way’s six-part documentary series “Wild Wild Country” (2018) for a thought-provoking exploration of the above themes. The documentary follows the events that took place when a commune comprising followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, an Indian spiritual guru, built the utopian town of Rajneeshpuram in Antelope, Oregon, in 1981. Soon thereafter things take a dark turn, as the six-part documentary series unfolds the theme of acceptance by state and church by illustrating the conflicts between Bhagwan’s ‘sanyassins’ (followers), local ranchers and the U.S. legal system. The root cause of these conflicts was the growing political power of Rajneeshees in Antelope in addition to their unorthodox religious beliefs and practices. As a result of these conflicts, what followed was the first and largest bioterror attack in the United States, murder attempts and allegations of immigration fraud, arson and illegal wiretapping.

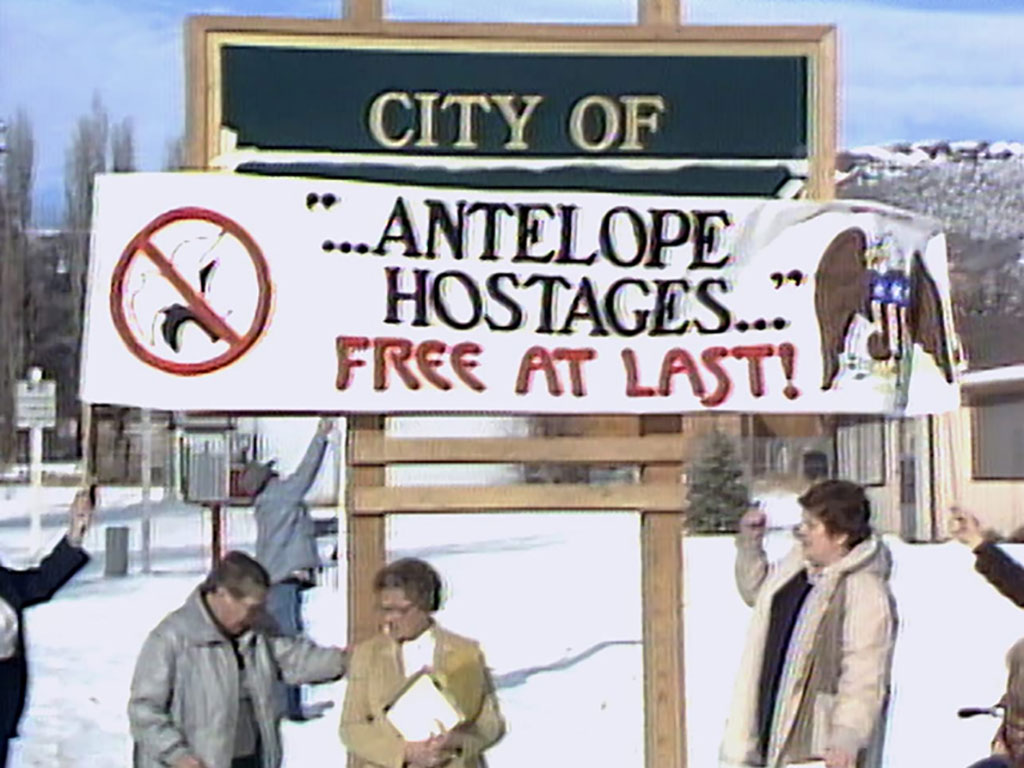

Even though today Rajneeshpuram is a long-forgotten part of American history, the events of “Wild Wild Country” resonate profoundly with the treatment of immigrant populations in the American society today. The documentary further reminds us of the dire need for separation of church and state for the safeguarding of freedom of speech in a democratic state.

The series contains interviews with key figures involved in the conflicts surrounding Rajneeshpuram, including extensive testimony from Ma Anand Sheela, Bhagwan’s trusted secretary and a key figure in the controversies against Rajneeshpuram; she describes a bioterror attack through salmonella poisoning of food in local restaurants. While Sheela’s accounts of the 1981 events are given a significant prominence in the documentary, the Way Brothers carefully balance the narrative with additional interviews of Antelope residents, followers of Bhagwan, attorney generals and investigative journalists who were all present in the events that led to the eventual collapse of Rajneeshpuram in 1988.

However, the documentary does not convey information through interviews alone. The cinematic image quality and wide frames shot on RED Dragon 6K — when contrasted with the Way Brothers’ use of blurry, low resolution archival footage to represent the actual historical events — add visual depth to the documentary by illustrating a distinction between the past and the present.

The narrative of “Wild Wild Country” is rhythmically edited together through hours of archival footage acquired from previous documentaries, broadcast services and television interviews about Bhagwan and Rajneeshees to accurately represent the attitudes towards Rajneeshpuram. For instance, in the first episode, the local ranchers describe how Bhagwan purchased an 80,000-acre ranch in Antelope and arrived in his Rolls-Royce like a king, along with his several thousand followers. These descriptions are supported by archival footage to create an impartial and accurate visual representation of the initial sentiments towards Rajneeshees. Such strategic use of archival footage throughout the docu-series is used to reinforce the intolerance of the local white populations toward Rajneeshees and their unorthodox beliefs such as free sex, universal religiousness and prioritization of science over religion, which conflicted with Christian values.

Such conflicts between Antelope locals and Rajneeshees prompted the eventual intervention of the state and the law. Beginning in episode three, the film pointedly approaches the theme of separation of church and state by craftily juxtaposing interviews of both sides to balance the story and intensify the conflict. According to the Rajneeshees, the state was intolerant of their spiritual beliefs and their growing political power in the state of Oregon. On the other hand, according to the interviews of state attorneys, Rajneeshees manipulated the law to commit immigration fraud to settle in the U.S. As both sides narrate their accounts, the discrepancies in the sociocultural and political ideologies of the U.S. democratic system become apparent especially with regard to rights of marginalized groups – homeless people, immigrants and religious minorities.

As is evident from these broader critiques, the underlying debates of “Wild Wild Country” go much deeper than just a historic overview of these incidents. Exploring themes of religious fundamentalism versus the freedom of expression, “Wild Wild Country” opens up a significant debate of the 21st century to portray the existing atrocities against the minorities existing in the U.S. This narrative not only depicts the internal hierarchical structures of the Rajneeshees but also highlights the external pyramid of the U.S. state laws that impact the democratic rights of the immigrants and minorities within the U.S.

Though there have been various representations of Bhagwan and his commune in the past, what sets “Wild Wild Country” apart from these earlier versions is that it does not merely depict the practices and spiritual beliefs of Bhagwan. It delves into the legal, political and social intricacies by avoiding definitive answers about who was right or wrong in the controversies surrounding Rajneeshpuram. The goal of “Wild Wild Country” is to make us realize that in a clash between church and state, what is at stake is the agency of individuals at the hands of institutional power. In the final episode, the mental and physical torture that the law enforcement agencies put Bhagwan through before he quits the dream of Rajneeshpuram leaves us wondering whether the coexistence of church and the state is possible, and whether law can maintain its neutrality for protection of vulnerable populations in a democratic country like U.S.