'Would you like to see handicapped people depicted as people?' A Review of Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution

“Crip Camp” (LeBrecht, Newnham, 2020) opens with a close-up of a reel-to-reel tape deck as the voice of the system operator teaches campers how to use a Sony PortaPak camera: “I’m recording now. If I want to turn it off, I need to press the trigger again …”

This is immediately followed by a camper in a wheelchair utilizing this novel technology. Holding a microphone, with a coy smile and a newscaster’s bravado, he interviews another camper with disabilities, asking, “Would you like to see handicapped people depicted as people?” With quick and skillful comedic timing, the other camper sardonically replies, “Excuse me?” They laugh.

These first 30 seconds of the documentary encapsulate the core of “Crip Camp,” an immersive documentary about the interwoven processes of disenfranchisement and sociopolitical change. Immersion, here, denotes immediate access for viewers to the feelings and emotions of the subjects through the careful arrangement of the sights and sounds of Camp Jened, a summer camp in the Catskill Mountains for teens with disabilities. Supported by the Sundance Institute and released by the Obamas’ production company, Higher Ground, “Crip Camp” immerses viewers in the subtle nuances that underlie major processes of social change.

Mirroring the uncertainty most campers experience on their first day at sleep-away camp, the opening of “Crip Camp” effectively disorients by plunging viewers into the Woodstock-esque chaos of Jened. Using long-forgotten footage from the People’s Video Theater’s 1971 excursions to Camp Jened, co-directors Nicole Newnham and former Jened camper Jim LeBrecht spend the first half of “Crip Camp” documenting the untold story of how this unique space for teens with disabilities contributed to their development of selfhood, power and agency.

The campers were not activists when they arrived at Jened. They were teenagers with the same interests as their peers, longing for community, friendship, laughter, art, music and sexual connections. They were rebellious and sought power over their own lives.

The People’s Video Theater, an activist and artistic video collective in New York City, decided to document Jened after hearing reports of a crabs outbreak. Their footage shows the immediate response and aftermath: All of the clothes, mattresses and sheets are strewn across the lawn; separated groups of male and female campers stare over to each other from the porches of confined bunks. Quarantined to combat the outbreak, a camper strums on his guitar, singing, “I got those poor old crab blues.”

Several young men and women are interviewed — most of them are giddy with excitement. Why? Because this outbreak serves as evidence of their sexuality and is a testament to their agency as human beings, breaking down sexual stigmas that still afflict the disabled community today. In interviews, campers describe Jened as the site of their first sexual experiences. Outside of the hippie haven of camp, campers were desexualized and asexualized by their communities. In the words of one camper, people with disabilities are too often denied gender and sexuality, “not being seen as a man or woman, but rather just as a wheelchair.”

Although “Crip Camp” is ultimately about how campers from Jened became leading participants in the establishment of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the film does not initially reveal this narrative. Rather, the film allows the viewer to experience the campers’ varied transitions from being children with disabilities in mid-century America, to teenagers at Jened, to activists for disability and human rights. The narrative unfolds as if in real time; the campers’ development is presented to the viewer without the privilege of hindsight.

The second half of the film moves away from Camp Jened and begins to document former campers’ successful efforts as activists. Following a host of Jened campers as young adults, the film traces those who played a significant role in the enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act, such as disability activist Judy Heumann. “The problem” with discrimination against people with disabilities “was people without disabilities,” says Heumann, who in the first half of the film is shown as a camper polling a large room of her peers about dining options for the upcoming week. Even in the earliest footage of Judy, viewers witness her insistence on letting all voices be heard and giving everyone a chance to speak, a quality that foreshadows her passionate speeches while organizing demonstrations on the streets of Manhattan and fighting for the enforcement of legislation during the 504 Sit-in in 1977. With more than 150 participants, lasting 25 days, this is still the longest-ever sit-in in a federal building. “Crip Camp” demonstrates that the seeds of Heumann’s leadership were always there, but the opportunities afforded at Jened allowed her to develop as both an individual and a leader.

“Crip Camp” is a story of both personal and communal liberation that highlights the trajectory of sociopolitical change from the nonconformist hippie roots cultivated at Jened to the implementation of practical policies by former Jened campers. The film incorporates and honors late-1960s and early-1970s aesthetics through the directors’ explicit mission to celebrate the punk and outsider art philosophies that contributed to the freedom felt by campers. Viewers are invited to relive this feeling with campers due in large part to the media incorporated throughout the film, such as the campers’ self-recorded footage and LeBrecht’s meticulous sound design. The self-recorded footage immerses spectators in campers’ self-actualization, serving as a vehicle for the campers to find and develop their own voices.

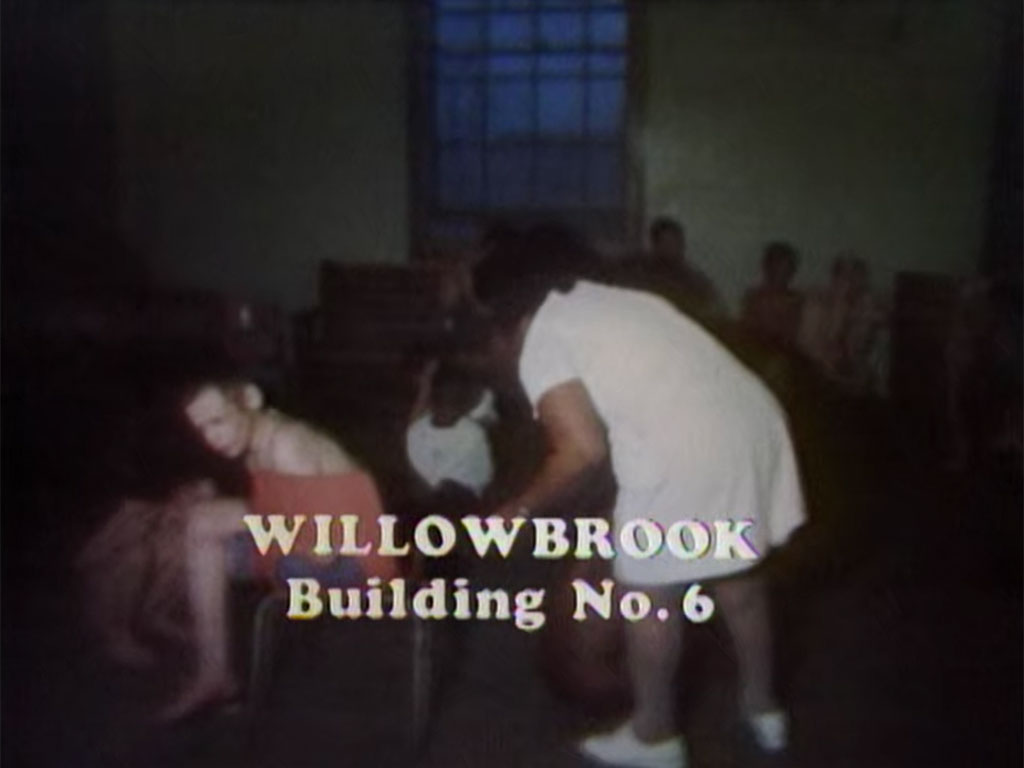

The sequences that focus on Steve Hoffman, a camper with cerebral palsy, embody the punk aesthetics so central to Jened. Whether supporting his peers by acting as a sounding board for those who are struggling to communicate or performing burlesque at San Francisco’s Mabuhay Gardens punk club, the rebellious, tough, ironic, yet extremely loving Hoffman is shown inspiring other campers to fight against a world that “wanted them dead,” a sentiment reinforced by the violent neglect shown in the film through footage of institutions like Willowbrook.

The moments caught on tape in 1971 by a young LeBrecht seem insignificant to his friend and fellow camper, Valerie, as he films the outside of the “Girls 1” cabin. Smiling, she approaches his wheelchair on crutches and asks into the camera, “Is this necessary, I mean, is this important?”

How could Valerie realize the importance of this recording? Think back to any video you made when you were a teenager at camp: Would you ever predict that it would serve as footage for an untold story of how individual people enact true systemic change? “Crip Camp” not only shows us that change is possible — it is a deeply personal and powerfully political document of the crucial context in which those who enacted change developed, learned and ultimately, became who they wanted to be.